The Buffalo Jump: Hunting with Gravity, Native American Style

It is often said that the Native American peoples of the great plains of North America were, and are, in tune with their landscape and their environment. Few understood the land around them as well, few adapted their lifestyles so closely to match its generous and its lean periods. And few used it as efficiently in hunting for that great creature on which they so depended, the buffalo.

It is often said that the Native American peoples of the great plains of North America were, and are, in tune with their landscape and their environment. Few understood the land around them as well, few adapted their lifestyles so closely to match its generous and its lean periods. And few used it as efficiently in hunting for that great creature on which they so depended, the buffalo.

You might think such an enormous, powerful and fast creature would be difficult to hunt. And you would be absolutely right in thinking this: an adult North American buffalo can weigh up to 1,179 kg (2,599 lb), bigger and heavier than anything else on the continent barring the moose in the far north. They were extremely difficult and dangerous to hunt, but the reward in meat and hide was immense.

But how to bring down such an immense beast? And, more importantly, how to do so safely?

The answer, a solution found in multiple spots across the great plains of America, is what is known as the Buffalo Jump. This ingenious use of the existing landscape represents a fascinating aspect of Native American hunting practices in Pre-Columbian America.

The Importance of the Buffalo

Before delving into the specifics of the Buffalo Jump, it’s essential to understand the central role that the buffalo, or American bison, played in the lives of many Native American tribes. For these communities, the buffalo was much more than a source of sustenance; it was integral to their culture, spirituality, and survival.

- Bighorn Medicine Wheel: More than America’s Stonehenge?

- Desert Kites: Prehistoric Geoglyphs of the Old World

Nor was the Buffalo Jump the only approach. Native American hunting practices were diverse and adapted to the varying landscapes and ecosystems across the continent.

These practices ranged from solitary stalking and the use of snares and traps to the communal drives and sophisticated techniques like the Buffalo Jump. The Buffalo Jump was perhaps the most effective method used by indigenous peoples of the Plains to hunt buffalo: driving them off a cliff, allowed hunters to approach and kill any survivors more easily.

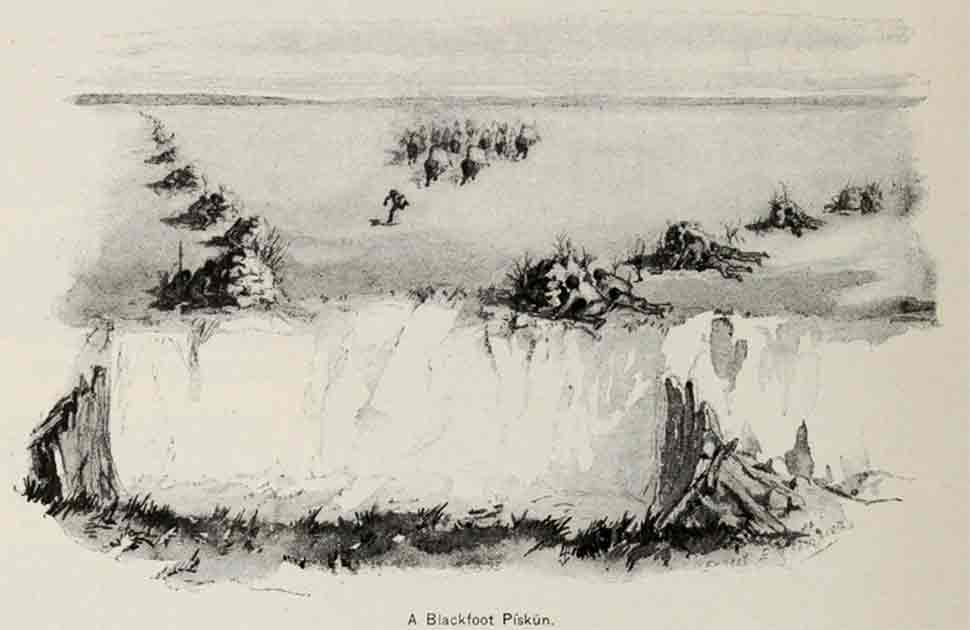

The process of a Buffalo Jump required meticulous planning, deep knowledge of buffalo behavior, and coordinated effort among the tribe’s members. Hunters would identify a suitable cliff (the titular “buffalo jump”) and then create a funnel-like structure using rocks, branches, and other natural materials.

This structure was designed to guide the buffalo toward the cliff’s edge. Young men, known as “runners,” adorned in buffalo skins, would then provoke the herd and lead them toward the jump, mimicking the sounds and movements of the animals to create a sense of urgency and panic. As the buffalo stampeded towards the cliff, the animals would fly over the edge and be killed in the fall. Other, more experienced hunters waited below to quickly kill any injured animals.

But the Buffalo Jump was not merely a hunting technique; it was imbued with significant cultural and spiritual dimensions. Many tribes performed rituals and ceremonies before and after the hunts to honor the spirits of the buffalo and the land.

These practices underscored the deep respect that Native Americans had for the buffalo, acknowledging the sacrifice of life that sustained their own. The communal nature of the Buffalo Jump and the subsequent distribution of meat and materials among the tribe reinforced social bonds and ensured the survival of the community through shared resources.

But this was first and foremost a practical solution to provide for the tribe, and a necessarily gory one at that. The names of the locations used for such hunting are a testament to the gruesome affair.

But that is not to say that the Buffalo Jump sites did not demonstrate a profound understanding of ecological balance and sustainability. Native Americans were keen observers of their environment, developing practices that ensured the long-term health of the buffalo populations and the ecosystems they inhabited.

Wendigo: Cannibal Beast of Native American Legend

Moncacht-Apé: Did this Yazoo Conquer the Wild West First?

And there is much to be learned from such sites. The scenes of such mass slaughter would necessarily require large-scale processing camps nearby to ensure nothing was wasted.

Archaeological evidence from such sites can be therefore very revealing about the pre-Columbian Americans who used the locations for hunting. In particular it revealed the frugality and efficiency in how the Native Americans of the great plains used their kills.

The meat from the animals would be separated and either processed for immediate use, or preserved in the form of “pemmican”: a calorie-rich mixture of dried meat and tallow. The hides would be stripped of fat and used for clothes and shelter, the animal’s bones for tools.

As we face contemporary challenges of biodiversity loss and environmental degradation, the principles embodied in the Buffalo Jump and similar practices remind us of the need to learn from the past to ensure a viable future for all species, including our own. Through studying and honoring these ancient traditions, we can better appreciate the complexity and sophistication of Native American cultures and their enduring legacy in shaping our understanding of the natural world.